Writing Paragraphs: Building Blocks of Prose – By: Robert Waldvogel

Writing Paragraphs: Building Blocks of Prose

By Robert Waldvogel

INTRODUCTION:

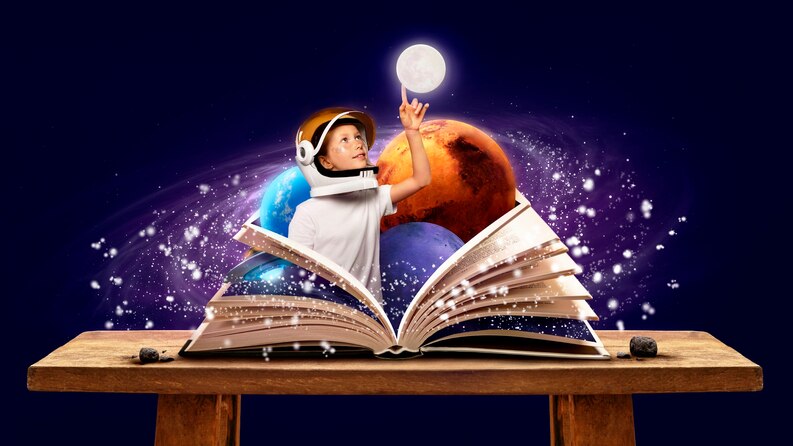

While words can be considered the individual units that make up sentences, sentences themselves are the components that comprise paragraphs. As the building blocks of prose, whether it be of the nonfiction, memoir, autobiography, flash fiction, short fiction, or novel genre, they have form, structure, and purpose. This article will examine all three.

PARAGRAPH PURPOSE AND STRUCTURE:

Visually, a paragraph appears as a block of sentences, usually with the first line indented. That indentation signals the beginning of each subsequent one within the text.

“As a reader, you identify the paragraph at a glance, just by its appearance,” according to Carol Pemberton in her book, “Writing Paragraphs” (Allyn and Bacon, 1997, p. 1). “Paragraphs vary considerably in length because they vary in content and purpose.”

Organizationally, they enable the writer to focus on a single main idea, which can be both clarified and supported by one or more relevant points. Linked by a second or related idea, the succeeding paragraph does the same, and collectively they illustrate a longer, more encompassing idea or theme, as would be expressed in an essay, a term paper, or a nonfiction book’s chapter.

Paragraphs can contain both general and specific statements, such as the following.

General: Movies can be suspenseful.

Specific: Movies, such as Die Hard and Die Hard 2, with their fast-paced action, can be suspenseful.

The second example is specific because it names two movies and explains why they are suspenseful.

General statements, which are prone to reader interpretation, can summarize the main idea in each paragraph, but specific ones enable him to focus on a specific feature of the main idea.

Properly structured paragraphs contain two integral elements.

1). A general topic sentence, which usually appears first, that states the paragraph’s main idea.

2). One or more specific sentences that support and illustrate the main idea.

Consider the following paragraph, whose topic sentence appears in boldface type and whose supporting sentences appear with standard imprints.

“There are ways to save on airfare. Not all seats on all flights carry the same price tag. If you book early enough, for example, you can usually find a lower fare, because the seats set aside for it are still available. Since most people travel on weekends, flying mid-week, such as on a Tuesday, or a Wednesday, will secondly offer the lowest fares. Finally, if you fly during less popular seasons, like the winter, you can take advantage of the lower fares airlines offer to fill traditionally emptier airplanes.”

Aside from a paragraph’s basic structure, it should also incorporate other elements. One of them is unity.

“When applied to paragraph writing, unity means the paragraph is about one primary idea,” emphasizes Pemberton (ibid, p. 7). “All the statements in the paragraph have to do with that one idea. The writer does not wander away from the idea, but rather stays with it and leads readers to a clear understanding.”

As illustrated by the previous example, the topic sentence, like an introduction to what was to follow, stated that there were ways to save on airfares and the supporting ones, maintaining unity about the subject, gave three methods of doing so.

Another important paragraph element is support or development-that is, does the writer support, develop, and almost prove his topic? If, in the previous example, discussion following the main theme entailed the best Florida hotels, there would have been no relevance to it.

Yet another element is length. Paragraph length itself depends upon the topic sentence and varies in accordance with the degree of development resulting from it or the amount of support required to illustrate it.

Finally, the concluding statement either offers a proving, lasting thought or a restatement of the topic one.

PARAGRAPH TOPICS:

While school students may have little choice as to the topics they must write about because of curriculum complying assignments, others, particularly freelance authors, are virtually limitless in what they can explore in paragraphs and the longer pieces of which those paragraphs are made.

Nevertheless, they should consider several aspects before they attempt to transform ideas into words.

Interest, knowledge, experience, and abilities, first and foremost, should serve as the weathervanes that point to potential subjects. If a person has an interest in something, it is likely that it has led to his knowledge of it, possibly through study, and even his personal experience with it, qualifying him to explore and explain it in written form.

If, on the other hand, it is not possible to select a topic, the writer can always take the designated one and approach it from a new, fresh, or different angle.

Purpose is another aspect. Although a school assignment can certainly constitute a “purpose,” other, not necessarily mandatory ones can be to write, to inform, to offer advice or direction to others, to explain, to persuade, and to entertain.

Readership, the third, should always be considered when an author writes something, especially if his intention is to publish it. A school assignment, needless to say, will be read by a teacher or a professor, possibly for a grade. A travelogue in which the important sights in San Antonio, Texas, are discussed will facilitate tourist trip planning. And an article about rose garden care will appeal to those with such home flora.

Writing ideas themselves can result from internal inspiration, external stimulation, or brainstorming various possibilities, and then filtering, sorting, and grouping the points to be discussed.

THE DUAL PURPOSES OF TOPIC SENTENCES;

“The topic sentence states the main idea of a paragraph,” according to Pemberton (ibid, p. 35). “For that reason, it is the most important sentence in the paragraph. Writers build paragraphs to support topic sentences, and readers rely on their sentences to see which main ideas are being developed.”

The topic sentence itself serves two purposes. Firstly, it establishes and foreshadows the paragraph’s purpose. Secondly, it serves to narrow its scope by offering a controlling idea, creating the parameters to which the author should adhere so that information is relevant and does not stray from its purpose.

A topic sentence should lead to discussion and elaboration and presents an idea that is narrow enough to be adequately covered in a single paragraph, but should not be complete in and of itself without that proceeding paragraph.

Consider the following sentences.

“The principle value of writing for a student is that it improves his grades.” The last four words, “it improves his grades,” limits it to the points that can be discussed in that paragraph and sets up reader expectation that he will learn how it does so.

“Think of the topic sentence as a writer’s promise to the reader,” Pemberton advises (ibid, p. 36). “The writer promises to discuss a specified main idea.”

SUPPORTING A PARAGRAPH’S TOPIC SENTENCE:

While topic statements are general and sometimes short in nature, sentences that follow to support them should be specific and can be longer, since they usually present facts. They are intended to provide readers with clear, precise understanding.

General references often leave readers open to interpretation based upon their own experiences and understanding. “A well-paying position,” for instance, may mean $25,000 to an unemployed person, but a seven-digit figure to a wealthy one. Without specific figures, neither will ever know what it means to the author.

In order to support a topic sentence, the writer must use specific details, facts, examples, and even published quotes, such as “13.5 percent of Americans live below the poverty line,” according to the “Probing Poverty” article in the September 15, 2019 issue of News and Views magazine.

“Details provide support,” according to Pemberton (ibid, p. 62). “(They) are specific pieces of information that show what the writer means by the topic sentence. Examples illustrate a main idea. One or more examples might be used in a paragraph, depending on the general idea being supported. Facts are statements about which independent observers agree… Quotations are the exact words of a writer or speaker.”

PARAGRAPH COHERENCE:

Another important paragraph writing element is coherence. Coherence itself entails several aspects. Relationships between ideas, for instance, should be clear and connectable-that is, one should logically and smoothly flow from the previous one. Supporting ideas additionally explain previous statements. Main ideas can be expressed through repetition. Finally, text flow is ensured and enhanced by means of transition words, such as “but,” “however,” “nevertheless,” “therefore,” “for,” and “yet,” among others.

“Reading incoherent writing is like riding with a driver who is lost, who wanders up and down bumpy streets, hunting for a destination, but wasting time and jarring passengers around,” comments Pemberton (ibid, p. 68).

Consider the coherency of the following paragraph.

“I have just returned from a hectic day. My alarm, as usual, went off at 6:30 and I showered and dressed. It looked like it was going to drizzle so I brought my umbrella. There was hardly a drop in the sky, but everyone drove as if it was pouring cats and dogs and I was almost 15 minutes late to work. I found the report from my secretary on my desk. I think she’s having relationship problems, because she hasn’t been up to snuff lately. Maybe she didn’t sleep well last night. I had a night like that last week. Even the Tylenol didn’t help. Because of the traffic, I missed Harold’s opening comments in the meeting. He twice told me we’d go fishing some Saturday, but never seems to remember when I put him up to it. I wolfed down my lunch and almost had a fight with a client in the afternoon. I could hardly contain myself. The traffic was really crawling because of a downpour when I drove home. As I walked into the kitchen, I realized I hadn’t gone food shopping lately, so the cupboards were bare. I plopped down on the couch instead, still in my suit and tie, and fell asleep.”

Coherence can be enhanced with the proper use of transitional words, phrases, and clauses.

“Words, phrases, and clauses used as transitions are like bridges that carry readers safely from one point to another,” Pemberton advises (ibid, p. 72).

EXPOSITORY PARAGRAPHS:

Expository writing entails explaining, describing, illustrating (through words), and revealing, and appears in almost all genres, including fiction. While narrative writing can demonstrate actions, emotions, feelings, and moods through the conversation and interaction between two or more characters, its expository counterpart simply informs, as in “Regina and Dawn had a disagreement last night” or “The garden was a tangle of weeds.” It is certainly instrumental in writing paragraphs.

There are several expository writing techniques that can be used in and can even enhance paragraph creation. The first of these involved comparison and contrast.

“Writing with the comparison/contrast pattern, you examine similarities (comparisons) and differences (contrasts) between two people, objects, or ideas,” according to Pemberton (bid, p. 135). “The topic can be as abstract as socialism versus capitalism, or it can be as concrete as brand X versus brand Y toothpaste. Obviously for a single paragraph, the topic must be narrow enough to allow discussion of specific similarities and differences.”

Consider the following two examples.

Comparisons: “The small restaurant that opened in town last month is very much like a diner; the service is friendly, the food is simple and wholesome, and the prices are modest.”

Contrast: “Frayer’s wheat bread is similar to Hoffmayer’s: all-natural and baked with stone-ground wheat. On the other hand, it tends to be coarser and drier.”

Another expository writing technique is designated “process writing.” Ideally suited to how-to guides and instructional manuals, it presents chronological, step-by-step procedures, as in the following.

“In order to reupholster a chair, you first need to relocate it to a work area, such as a basement or a garage. You next need to remove the staples or tacks that keep the fabric affixed to the frame. Inspect the foam or stuffing under it after you have. If the chair is five or more years old, it may have begun to decay and you will most likely want to replace it. Measure the area it covered and cut the new stuffing according to the required size, tightly packing it into the chair’s crevices. The new fabric covering must also be cut to measured size. After you have, pull it around the chair’s frame tautly before re-stapling or re-tacking it in place. You may need a helping hand to pull one side of it while you fasten the other. Finally, return the chair to its original location.”

Another expository writing technique is that of classification. It enables the author to categorize objects, things, concepts, and even people, and then provides sufficient details so that the reader can understand the differences between them. Nevertheless, a single common denominator unifies the paragraph. Consider the following example.

“All published books are written, but there are differences between them. Those from the United States and the United Kingdom, for example, appear in English. However, words such as ‘harbor’ are spelled differently, with the letter ‘u,’ as in ‘harbour.’ When they are placed vertically on a shelf, their titles are read from the top to the bottom. Books in Germany are obviously in that language, but the titles on their spines are read from the bottom to the top. Those from Israel are neither in English or German, but appear in Hebrew, and are read from the back cover, which is actually the front one. Pages are read from the right to the left.”

In this example, “published books” constitutes the common denominator, but their spelling, language, spine printing, and reading direction serve as their distinctions.

Yet another expository writing technique is that of definition.

“Normally, definitions are very brief-just enough to explain a term or concept that is either unfamiliar or being used in an unusual sense… ,” according to Pemberton (ibid, p. 157). “Sometimes, however, an entire paragraph… will be devoted to an extended definition of a term. Because of the greater length, readers naturally expect that one meaning (or perhaps several meanings) will be elaborated on.”

Consider this example of a paragraph that offers a definition.

“The most common definition of the world ‘alone’ is to be somewhere without the company or presence of at least one other. But there is more to this concept than just existing on your own. If you are uncomfortable with, distrustful of, and therefore unable to connect with others, you are equally alone, because you cannot complete that person-to-person or soul-to-soul link. The definition extends beyond the sheer presence of another. Instead, it involves your ability to enter into a close bond with that person. If you are at a gathering with ten friends, for instance, yet cannot relate to them in any meaningful way, you can also consider yourself to be alone. Finally, if you try to approach someone and he or she either shows no interest in you or even rejects you, you can also consider yourself to be ‘alone.'”

Article Sources:

Pemberton, Carol. “Writing Paragraphs.” Needham Heights, Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon, 1997.

Article Source: https://EzineArticles.com/expert/Robert_Waldvogel/534926